The critical role of technology in the economic development of any country cannot be emphasized enough. Far-reaching in its scope and utility, the application of information and communication technologies (ICTs) fosters education, entrepreneurship, social impact and, therefore, leads to long-term human development.

Embracing technology especially in underdeveloped and developing nations like Pakistan can potentially lead to prosperity as it not only channels enterprise towards economic emancipation, it is a tool that has the potential to organically integrate gender inclusiveness in the economic mechanism of a country.

Pakistan is reputably one of the most notorious countries in the world when it comes to terrorism, inter-state ethno-religious conflicts and a flagging economy. That said, it is also one that has, in fact, produced some of the brightest minds – both men and women – into the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields.

Irrespective of the state of chaos in Pakistan, there is still light at the end of the tunnel. Sustainable growth can become a reality if instigated from the grassroots level.

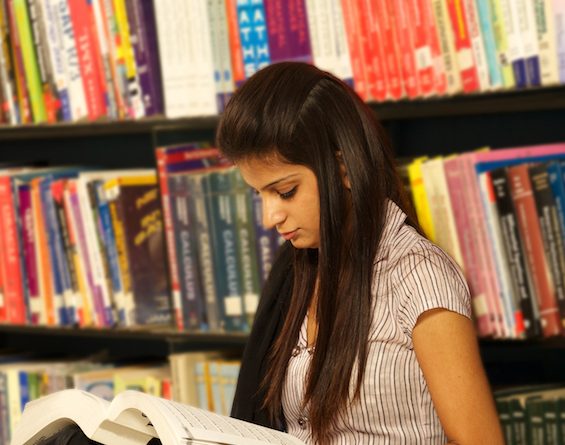

Education across the board for both men and women is a fundamental pillar for creating knowledge-based societies – a notion conspicuously absent from patriarchal societies and derailed economies.

The 21st century is abuzz with notions of integrating women in the global economic mechanism. With the inclusion of a billion women into the workforce globally in the next decade, the female gender is hard to ignore. Bringing this perspective to the national front, the importance of including women into the conversation – especially in STEM fields – in not only critical, it can in fact be considered life-saving.

Analysts believe countries marginalizing women are those inundated with issues of terror and conflict. Pakistan is a country replete with years of conflict, making it difficult for foreign investment as well as entrepreneurship to take root. In order to move forward, the need of the hour is to diversify, educate and then mobilize human resources including women. Until women play a participatory role and engage in national as well as economic discussions, in decision-making positions, positive change will be next to impossible.

Education across the board for both men and women is a fundamental pillar for creating knowledge-based societies – a notion conspicuously absent from patriarchal societies and derailed economies.

According to an article titled “Gender as a social determinant of health: evidence, policies, and innovation” written by Gita Sen, and according to Piroska Ostlin in her “The Women, Gender & Development Reader”, “Barriers to education of girls include negative perception about women that devalue their capabilities, strong beliefs about the division of labour that places inequitable burdens on females, gender-biased beliefs about the value of educating girls and the curricula that as seen as inappropriate for girls.”

Talking about the state of education in Pakistan, the late social activist Sabeen Mahmud told Ananke during what is perhaps one of her last interviews, “There are so many societal factors at play. It is already understood that more men will pursue careers in engineering and technology than women. Having said that, there is also more awareness today than there has ever been. Yes, definitely, work needs to be done at the grassroots level for any issue to have advocacy and activism. I think it’s important to fully understand the complexity of the issue. People will generally say our problem is education. If we had education things could be a lot better. But fact is there are more issues at play: class issues, poverty etc., so you can’t really look at things in isolation. I think understanding that this is a grave systemic issue that has all kinds of problems rising from it. And it all really boils down to who will take up the responsibility and work on it. There are people who can make a difference on individual level as well. People just want solutions without trying to understand what the problems are.”

Talking about the state of education in Pakistan, the late social activist Sabeen Mahmud told Ananke during what is perhaps one of her last interviews, “There are so many societal factors at play. It is already understood that more men will pursue careers in engineering and technology than women. Having said that, there is also more awareness today than there has ever been. Yes, definitely, work needs to be done at the grassroots level for any issue to have advocacy and activism. I think it’s important to fully understand the complexity of the issue. People will generally say our problem is education. If we had education things could be a lot better. But fact is there are more issues at play: class issues, poverty etc., so you can’t really look at things in isolation. I think understanding that this is a grave systemic issue that has all kinds of problems rising from it. And it all really boils down to who will take up the responsibility and work on it. There are people who can make a difference on individual level as well. People just want solutions without trying to understand what the problems are.”

Adding she said, “We should also look at issues stemming from societal pressures. The ground reality is that women have greater pressure to get married. There are very defined gender roles that women have to take care of such as the household and family. Even progressive families who agree to let women work, expect them to ensure that the household is running smoothly. So there are tiers of expectations. In order to see women grow professionally, it is crucial to have the family onboard.”

In a 2012 report by Pakistan Software Houses Association for IT and ITES (P@SHA), it was revealed that “Women constitute around 49 percent of the total population of Pakistan. However, their participation in the overall labour force of the country remains low. This is due, in part, to their marginalization within public, private and professional spheres based on factors such as age, marital status, number of children, level of education achieved, household economic status, patriarchal family structures, customs and traditions in the areas where they reside. Due to this marginalization and resultant low levels of economic participation, women in Pakistan represent only 14percent of the total labor force according to the 1999-2000 Labor Force survey. Compared to other countries in South Asia, such as Bangladesh (42 percent), Nepal (41 percent), India (32 percent), Bhutan (32 percent) and Sri Lanka (37 percent), the proportion of women in the workforce in Pakistan is the lowest. Further, according to the South Asia Research Program’s report ‘Women and Paid Work in Pakistan’ the proportion of women in white collar jobs in non-traditional areas such as engineering, banking and law remains significantly low.”

The hurdles in the way to prosperity in Pakistan are many. Patriarchal norms and traditions become major hindrances when it comes to women actually going out to work. More specifically, sectors which were traditionally male dominated have very low participation of women. This can be attributed to a number of reasons: from familial issues to the simple logistics of travelling and staying late in the office in a country overwhelmed with security issues.

The proportion of women in white collar jobs in non-traditional areas such as engineering, banking and law remains significantly low.

“There are many other problems especially in the city of Karachi where people are scared to drive alone. So there are logistical issues which are hampering progress as far as Pakistani women in STEM are concerned,” Sabeen had remarked.

Adding, she said, “It is important to acknowledge the fact that the Internet has played a remarkable role in empowering people with 75 percent mobile penetration which is how it has created such an impact. Given the tragic situation of Pakistani politics, people are actually fed up with all that and are now looking at ways of making a difference on an individual level. This change has also seen a rise in home-based businesses. Women especially are beginning to think that they can do this: stay at home, take care of the family and at the same time have a business and remain productive professionally.”

Agreeing with Sabeen, Yasmin Malik, Visiting Lecturer at Institute of Business Administration Pakistan & Freelance Telecoms Analyst, opined, “I don’t have a figure for it, but generally the percentage of women in STEM fields is low – although there are more women and girls in the area of Computer Science. At IBA, for example, we have at least a 35 percent female intake for our BSc in Computer Science program. In the field of medicine, the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC) has abolished the merit-based admission policy for medical colleges and for admission in 2014-2015 has instead reserved 50 percent seats for boys and 50 percent for girls. The prevailing trend till 2014 for applications to medical colleges in Pakistan was over 70 percent women – hence, the new policy will forcibly cut back the women intake by 20 percent. The PMDC argues that its decision was based on, to quote ‘the growing trend among girls of acquiring medical education, coupled with their tendency to leave the profession after having done so or not joining it at all.’ Hence cultural biases and norms mean that even though a reasonable number of girls acquire STEM-based education in Pakistan, many of them do not or are not able to practice after graduating.”

Economic emancipation can become a reality with Pakistani women potentially making headway in STEM fields only if, as Sabeen suggested, key questions and issues creating roadblocks are ascertained and people take responsibility for finding solutions. A general consensus for women participation has to be reached by all stakeholders – from the family to movers and shakers of the corporate world – for Pakistan to progress.

True education and training are stepping stones towards growth, but constantly gnawing issues such as the real participation of women can only be solved by not only utilizing ICTs as empowering tools of development, but also engaging the opposite sex in decision-making and leadership roles for gender diversity is vital to innovation and, therefore, lasting prosperity.